The consequences of privacy features and regulations for consumers

Ever since Apple rolled out ATT I’ve been asking friends to click “allow tracking”. In this article, I explain why—like I do to my non-marketing friends.

Nearly two years ago, I was having dinner with a couple of non-marketing friends. This was around the time when we were first seeing the impact of Apple’s ATT (App Tracking Transparency) on Apple Search Ads revenue. I explained to them what was happening, and by the end of the night, they were fully behind accepting tracking / cookies from then on.

I had the idea for this article then, but never got around to writing it. As more and more companies implement “privacy features” (by the end of the year, Google will be phasing out cookies) and as Apple enters an antitrust battle, this seemed as good a time as any. So let’s get to it.

A quick background on privacy changes

Over the last few years, a number of privacy features and regulations have been implemented. They aimed to tackle issues such as personal data selling and data harvesting. Some of the implemented changes have been:

EU’s GDPR and Brazil’s LGPD: Government legislation that implements requirements such as requiring opt-in consent from users before collecting data.

Depreciation of cookies: Changes from browsers, such as Safari and Chrome, that phase out the usage of first-party and/or third-party cookies.

Apple’s Link Tracking Protection: Feature from Apple that strips tracking parameters (like UTMs and others) from URLs on Safari, Apple Mail and more.

Apple’s ATT (App Tracking Transparency): Feature from Apple that requires users to consent to sending their IDFA (Identifier for Advertisers) for each app they install, in order for the advertiser and the ad platform to measure advertising results (e.g. installs, sign ups).

Although there is no doubt that privacy is an essential right that should be protected, some of these features and legislations aiming that have had negative consequences for both consumers and businesses alike.

⚠️ Before we get into the consequences, a small albeit important disclaimer: I’m not a lawyer and this is in no way a legal opinion on regulations. This is just one marketer’s view on how privacy changes have impacted data collection, and how, in turn, that impacted business and consumers.

Data is essential to the advertising business model most content providers use

Most media publications, from established news publishers to small food blogs, generate revenue via advertising. That’s how they did it back in print days and even news providers that pivoted to a subscriber business model are reverting back. User data provides two values for advertising:

Audience information: Understanding the demographics of who make up your users (e.g. age, gender, income, etc) helps advertisers identify whether your audience matches their target audience. If it is, advertisers are willing to pay a higher cost to advertise on your site. If your audience is high value / high spending (e.g. a developer audience), then their advertising pricing can be increased even further.

Improved attribution: Tracked user activity enables advertisers to better attribute (measure) the impact of their campaigns. When results are “proven” via attribution, advertisers increase both budgets and bids on that platform.

Due to these two factors, in most (or even all?) cases, better data will lead to more revenue for advertising-driven businesses.

Better data will lead to more revenue for advertising-driven businesses.

Privacy changes are, by design, aimed to collect less data. That’s what they’re built for. However, restrictions on data collection are far from affecting all companies equally.

The negative consequences of privacy changes

Opt-in consent requirement strengthens the hands of Big Tech

Let’s start with one of the key changes of GDPR: the requirement of opt-in consent, a.k.a the cookie “wall” or “banner”.

Before a site can send data to third parties (to the advertiser), you need user consent to to do so. That means when you visit that small food blog for the first time, you need to go through the consent flow. There’s no doubt that, as a user, it’s very annoying to experience this every time you visit a new site.

But, how many times have you gone through this consent flow when visiting a site from “Big Tech”? When you’re using a Google product (YouTube, Gmail, Chrome), an Apple product (iOS, Apple TV) or a Meta product (Whatsapp, Instagram, Facebook), two facts are at play:

Consent has already been given: It’s possible you’ve granted consent when creating an account at Product A, so it’s no longer required when using Product B — because both data is being shared to the same data controller / owner, Big Tech X.

They’re the advertisers themselves: Let’s say you’ve chosen to not consent to sharing an app’s IDFA to the advertiser. You’re still sending the data to Apple, who’s also an advertiser. Because they can own the whole journey (with App Search Ads), there’s no way to deny data sharing in this case.

The only way you can not send data to Big Tech is by not using their products. And given their footprint in devices, cloud services, browsers — that’s pretty much impossible without disconnecting yourself fully

The “first party data” that’s gathered by Big Tech, and not by brands that use their services to sell products or advertise with them, is actively used as a competitive advantage. Amazon uses the data from third-party sellers to develop its own products and “beat” smaller businesses.

Apple’s ATT becomes an effective competitive advantage

Apple introduced ATT in April 2021. The consequence was immediately clear: ad platforms (that weren’t Apple themselves) could no longer measure the impact of iOS mobile app campaigns. That had two impacts:

Incomplete attribution: Without being able to stitch together the user journey with IDFAs, ad platforms could now no longer identify which users eventually converted. Even if campaigns were still being as successful, the reported number of results dropped steeply. This is one of the reasons why more advertisers invest in econometrics as an alternative way to measure results.

Worse performing campaigns: But it wasn’t just the reporting of the results that dropped, the actual performance of the campaigns also suffered. Because Meta could no longer identify which users were converting, the algorithm also lost its ability to optimise for the right audiences.

The year after ATT, Meta, for example, saw the first decrease in advertising revenue in its history. Because, obviously, when advertisers are having poor results or believe they’re having poor results, they shift budget. Some estimate that Meta lost $10 billion from the impact of ATT alone.

Nowadays, Meta’s revenue has mostly recovered due to server-side tracking: which sends personal identifiable information from the advertiser’s server directly to Meta, bypassing Apple. However, implementing server-side tracking is more complex for businesses and still not offered by many ad platforms. This brings further consolidation for the digital advertising ecosystem.

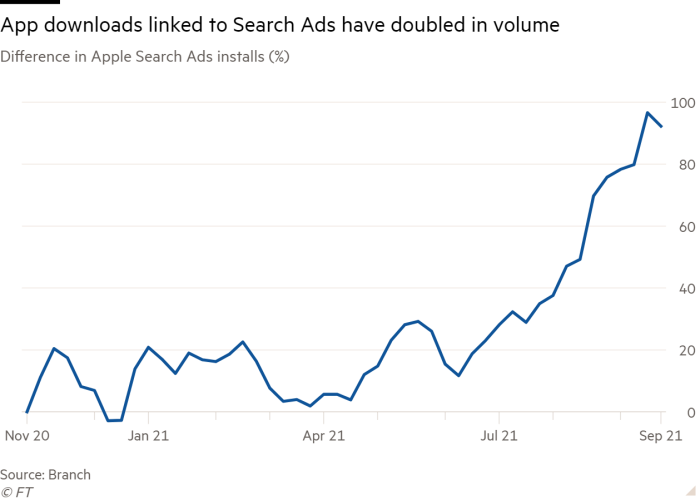

But what happened to the only ad platform that could still fully measure this user journey regardless of consent, you might wonder? Yes, Apple themselves saw a very different picture post-ATT.

Meanwhile, “privacy” has become an unique differentiator for Apple, cementing their status as a “customer-first” brand. A genius move or antitrust behaviour? I’ll let the regulators decide on this one.

Without data signals, smaller and/or niche brands struggle to grow

Over my career, I’ve executed paid media projects for brands that have really tiny budgets (like 5-person startups) and enterprises with gigantic budgets (Microsoft, Kraft Heinz, Adidas). And there’s a big difference on how companies of different sizes leverage marketing data for advertising.

The bigger the budget, the less advertising data / targeting capabilities you need.

When you spend millions of dollars a month, you don’t need data signals much. Your audience is so wide, and your strategies so varied, that a lot of the time you simply target users from a certain location within a certain age range. If you niche down on a certain group, you’ll mostly reach the same people with a zillion ads, or you won’t spend the assigned budget, which can create friction between marketing and finance teams.

It’s the small businesses and early startups that need better targeting and attribution the most.

When I led growth at Her in 2013-2015, a dating app for LGBTQIA+, Facebook Ads were our bread and butter. I can guarantee they were responsible for growing the product to its first million users (and now it has over 6 million users).

There was no other way we could reach such a scale of queer women elsewhere. A lot of them were young (still discovering their sexuality), closeted (with no online or offline presence in anything-queer) or living in rural / smaller towns. Mobile attribution and accurate targeting was what enabled us to grow. But this isn’t just the case for products for the queer community.

Direct-to-consumer products that serve niche audiences have struggled with growth since privacy changes. Apps for neurodivergent people, sportswear for women with different body types, etc. It’s a lot more difficult to launch and grow a longtail product today, ultimately giving consumers less choice.

Has it all been bad?

I believe privacy changes are strengthening Big Tech, harming small businesses, consolidating the digital advertising ecosystem, decreasing user experience and, ultimately, giving consumers less choices.

However, it would be naive for me to ignore some of the problems we’re facing due to the growth of digital assets and data Some privacy regulations have been, in my view, positive to consumers:

Right to be forgotten: where individuals can request past data (articles, images) to be removed from sites and search engines.

Set and maximum data retention periods: defines and limits how long organisations can keep data on users.

Right of access: Enables users to request personal data that is being stored on them.

To conclude, regulations can change and this renewed focus from the US/EU on antitrust legislation can prove fruitful. I hope future regulators involve industry professionals to craft legislation that protects consumers’ rights and privacy, while also levelling up the digital advertising field and ensuring a competitive landscape.

The intersection of marketing and data

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article on how changes to data collection impacted businesses and consumers alike, you’ll be happy to know that there’s more where it came from.

I write a free newsletter for marketers on how to best leverage data and you can subscribe below:

I agree with what you have to say. Regulation is very important but they shouldn't be the same for big tech and small businesses.